I’ve been thinking this for a while, but Uber integrating coach and train travel in their app is what convinced me to finally write an article on it. A transition to green infrastructure is essential. They’ll probably happen, but electric cars for everyone are the wrong way to go about it given the problems we already face with car dominated infrastructure. To get the best future, we need trains, and to get good trains, we need a solution to the “first mile, last mile” problem.

The first mile, last mile problem (or FMLM problem as I’ll call it from now) is the problem of the inescapable reality of public transport never taking you to your door. A well-connected train station in your local area is realistic, and the map of the UK’s railways before the Beeching cuts prove it, but there will always be people living in neighbourhoods without a train station. Buses can help fix this problem and it certainly isn’t fantasy thinking that everybody should live within 5 minutes of a bus stop, but they might not always be on the right route, and they present an extra challenge and delay for reducing emissions and car domination. That challenge is worth overcoming, but it’ll take time. Here is the FMLM problem – you can do the middle 200 miles of your journey by train with relative ease, but if the first and last miles are by foot, it is significantly harder and less appealing.

In the short-medium term, before we get these fantastic bus networks and huge railway expansion (if we ever get them) that shrink the first and last miles down to a few hundred metres, we need to address the FMLM problem by other means. In big cities, rental e-scooters try to do this, but whilst they solve some problems they also leave huge gaps. The users of these e-scooters is disproportionately young, white and male, there’s the issue of how they interact with pedestrians and cars, and disabled people and people with luggage can’t use them. I’m sure there’s an awful lot that I haven’t covered, too.

This means we are left with a system where, if we want the public transport system to be a fully functioning network that’s accessible to people, we need to embrace taxis. These allow people to take greater advantage of the railways even in bad weather or with luggage. They make travel more accessible for disabled people. They facilitate earlier and later travel, both by beating the bus timetables and by letting people feel safer than walking through city streets at midnight. But, unfortunately, they’re also a poorly regulated industry where safety violations are commonplace and discrimination is impossible to prove.

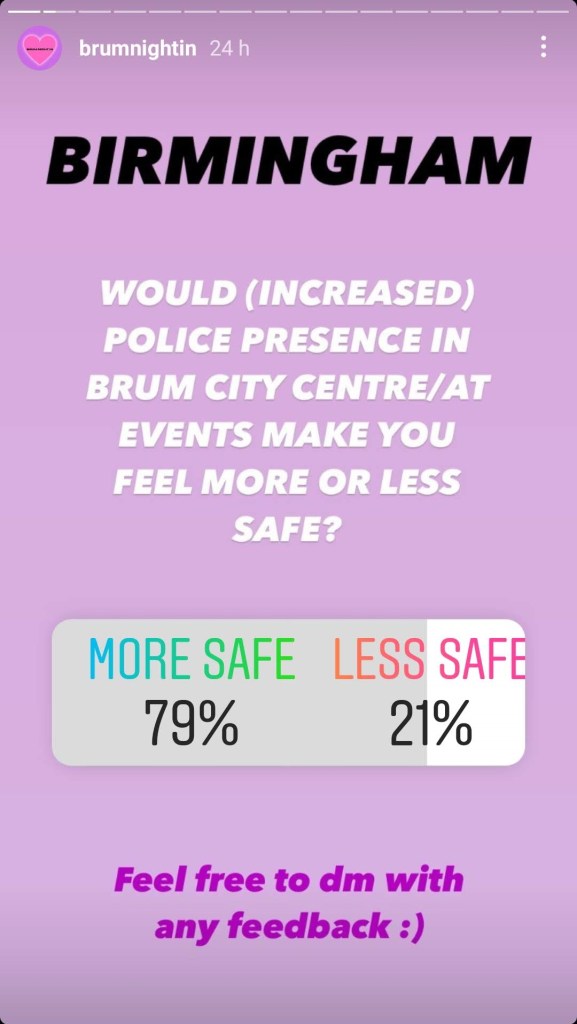

Let me talk about my own experiences, for a moment. A couple of months ago I was trying to get home after a night out from Birmingham’s gay village. I wasn’t particularly drunk, and the people I was with were at least coherent and not about to vomit. There we were, stood on the corner of a street in Birmingham, vulnerable. I took the photo at the top of this article. In the process of waiting for a taxi, we had two separate cars drive up to us and have their occupants shout “batty boys”; the passenger in one car filmed it. This didn’t fill me with confidence with regards to getting into a stranger’s car.

On top of this, there’s the issue of how difficult it is to even get a taxi from the gay village. Uber and Bolt drivers accept, then see you’re in the gay village, and reject it. This rejection is the best outcome, too – if somebody’s too uncomfortable to pick me up from the queer bit of town, I’m probably not safe in their car. Accessing this crucial bit of infrastructure can be emotionally challenging for any sober person, let alone somebody in a vulnerable state. Even without this discrimination, taxis can be hard to access, with taxi ranks placed far away from the clubbing areas.

Then there are the conditions in a cab. A driver wearing their seatbelt, not using their phone, and not vaping is the exception to what I am used to. I don’t want to have somebody’s vape in my face, but passengers are often not in a position to request the driver stops doing something in their car. The same goes if I feel unsafe with their driving – what are my options, especially given they have my home address? This power imbalance and lack of oversight leads to some significant issues for passenger comfort and safety, undermining trust in taxis.

These five things – vulnerability, unreliability, discrimination, difficulty of access, and power imbalance with no oversight – all combine into what I consider the taxi problem. This is the exclusion of some vital infrastructure from public thought and/or policymaking priorities due to it not being seen as vital and/or infrastructure, leading to issues including but not limited to access, safety, and quality. These themselves can lead to a reluctance to engage in the systems they include, with people being less likely to want to use public transport for a journey. The FMLM problem therefore isn’t resolved despite the technology existing for it, because the systems which FMLM transport relies on suffer from the taxi problem.

Whilst these five aspects are specific to taxis, the broader concept of the exclusion of infrastructure from public thought leading to poor outcomes and engagement is by no means exclusive to the area of transport. It can be applied to pharmacies for example, where there is little NHS oversight and poor quality results can undermine confidence in the healthcare system as a whole. Regardless of the service it is being applied to, it is a concept worthy of more exploration as it is, as we speak, limiting the future potential for adapting systems due to undermining public confidence.

Without addressing the taxi problem by, amongst other things, increasing standards, reducing discrimination, and introducing proper oversight, we will struggle to move into a future where public transport can be relied on. We will continue to have high A&E and GP waiting times as pharmacies and walk in centres aren’t relied on and preventative care doesn’t meet its full potential. We will have public services where things that should have been resolved sooner weren’t due to limited thinking around what critical infrastructure is, leading to a much bigger combination of social costs and tax burdens in the future.

The taxi problem is the biggest challenge we face precisely because nobody is talking about it. When the taxi problem enters mainstream dialogue, it will likely cease to be a problem at all.