As a quick disclaimer, this post deals with some pretty sensitive topics. Whilst I’ve done my best to approach them with care, please bear in mind that it obviously isn’t my intention to offend or blame anyone as you read on.

At the height of anti-police protests last summer, my Instagram feed was filled with people very honourably and justifiably calling for the police to be defunded. The big issue on every university student’s mind was – rightly – the killing of Sarah Everard. Even for me, a white able-bodied man, it was impossible to escape the reality of the fear that women felt. A serving police officer had killed a woman. At the time I posted on Instagram highlighting the lack of “good” cops in the Met. Why shouldn’t women and men be calling for the defunding of the police as an institution when its officers have killed women and criminalised vigil?

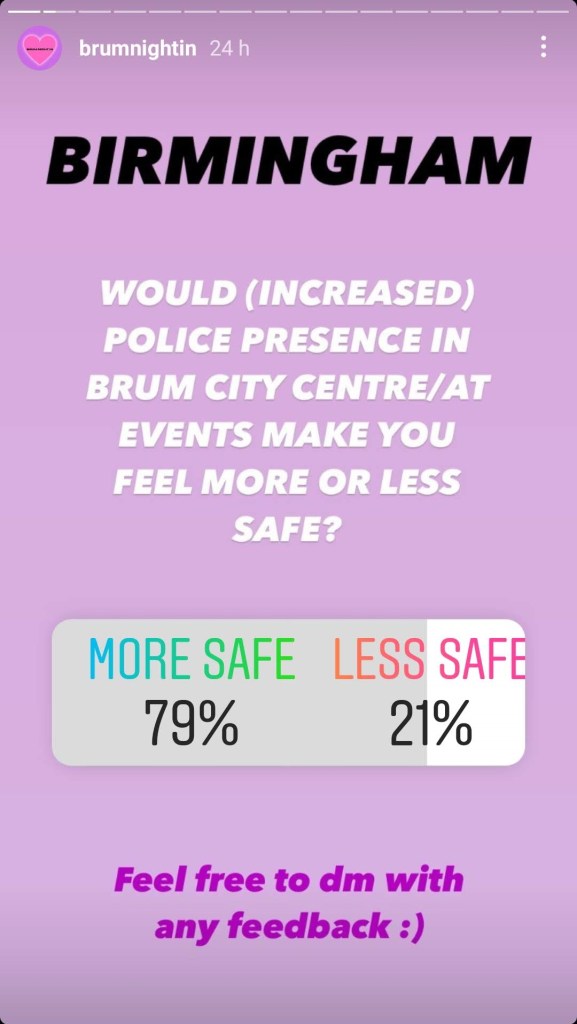

Fast forward to the return to universities this year. For my year group, it’s the first time clubs have been open when we’re at uni, and for the year below (and anyone born after March in my year group) it’s the first time they’ve been open since they turned 18. The issue on everyone’s mind is no longer Sarah Everard, but rather the fact that people – predominantly women – are being spiked by injection at an insane rate. A couple of weeks ago it was impossible to scroll through my Instagram stories without seeing another innocent person be spiked with a needle. A student group was set up at my university, on Instagram @brumnightin – calling for a boycott of clubs that don’t do enough to keep women safe. A couple of weeks ago, they posted a poll on their Instagram story – and these were the results.

The student population of Birmingham were, once again very rightly, saying that an increased police presence would make them feel safer. It would make me feel safer, so these students can’t be blamed.

That said, suddenly a student population that had appeared to overwhelmingly support defunding the police in summer had switched to wanting more police that winter. This is the embodiment of Instagram activism – a phenomenon significant enough that a fair few people will be familiar with the term already. I don’t seek to blame anyone here – I was the same: wanting to get rid of an institution that has, bluntly, shown no respect for women’s rights, and wanting women to feel safer in clubs. There’s no easy solution to this; the way I see it, people called for the right thing twice, but the two things they called for are incompatible with each other. So the question is, why does this happen?

As a geography student who has previously studied sociology, I’m acutely aware of how spaces are designed to make us interact with them in certain ways, and I think this can be applied to social media to figure out why Instagram activism, in particular, is so toxic. My belief as to why arose during a conversation with my wonderful mentor, Aisling, as to why I thought Twitter was so toxic – there’s so many arguments. Despite the flaws of these arguments (and believe me, there’s a fair few), they provide opposing viewpoints. I came to understand that part of the reason Twitter has so many confrontations is because of the way the platform is designed – click on a tweet and the option to reply is front and centre, you can’t delete the comments on your tweets, and the platform centres short text-based exchanges.

Instagram is quite the opposite. The replies are out of the way, you can delete and disable comments, and the platform is based on images. The general idea is you see an image and you like it or you move on, and the user interface runs with that idea. There’s nothing encouraging you to reply, and nothing really encouraging you to read the replies. Even the phrasing – “Tweet your reply” versus “Add a comment” makes Twitter encourage conversation and Instagram indifferent about it. Sure, the conversations on Twitter aren’t necessarily the most pleasant, but at least they’re there. I even had them forced upon me because I tweeted about fonts.

This is where the bandwagon nature of Instagram activism comes in. If you see a broadly agreeable Instagram post or story, you don’t go out of your way to scrutinise it or disagree with it because you’re simply not encouraged to. You either like it or move on, and when so many people are liking it, it’s extremely easy to get swept up with the dominant view at the time. At the peak of an event, story after story can be filled with well-intentioned friends sharing ill-researched posts. An example that comes to mind is a post on the Israel-Palestine conflict that was widely shared last summer and included the following:

“They are not ‘fighting’, Israelis are the oppressors and Palestinians are the oppresseed and the situation is about anything but religion.”

@key48return on Instagram

This was, quite clearly, a sweeping generalisation about every Israeli citizen based on the actions of the Israeli government. It ignores the complex history of the region and the fear that many Israelis face in the name of standing up for the oppressed. It is one thing to say the Palestinian people are oppressed, but it is a different matter completely when you say every Israeli is the oppressor. Yet proud anti-racists shared it far and wide because they saw it as standing up for an oppressed group. And, to me at least, it seems this happened because of Instagram’s aversion to dialogue. You don’t come away from the post with a balanced view, because you don’t see a conversation – all you see is an infographic taking up half of the screen, with “Liked by someone you know and 300,000 others”.

So how can we fix this? Well, Instagram can fix it, at least partially, by offering more room for dialogue given that the platform is becoming an increasingly political platform which inevitably leads to it becoming a bigger echo chamber for at least some users. They probably won’t fix it though, given that the app has been based around big images with just a bit of text since its creation. That leaves the burden on Instagram users to be more willing to criticise infographics when they’re one-sided. Look at the account of a post before you share it – what’s the bias? It also needs to be understood that complex issues, whether it’s the police, race relations, or international conflicts, can’t be reduced down to a simple 10 slide Instagram graphic, and nor should they be. Issues like this need time, depth and nuance, and when they are discussed on social media they need dialogue at the very least.

This post was in part inspired by a Vox documentary on how colour schemes on Instagram have been used to make infographics look progressive when they are the opposite. You can watch it on their YouTube channel here.